Many metal parts fail not because of wrong material, but because shear stress was ignored too early. I have seen strong-looking parts crack, shift, or shear during real service.

Shear stress is the internal force that acts parallel to a material cross-section, and it plays a key role in how cast and machined metal parts carry load, resist failure, and stay reliable in service.

I have worked in investment casting and machining for over twenty years. During that time, I learned that shear stress is not just a theory topic. It shows up in shafts, pins, thin walls, and joints every day. When designers and buyers understand where shear stress comes from, they make better decisions early.

What Is Shear Stress in Mechanical and Manufacturing Terms?

Many engineers first learn shear stress from formulas. In real manufacturing, shear stress is easier to understand through behavior.

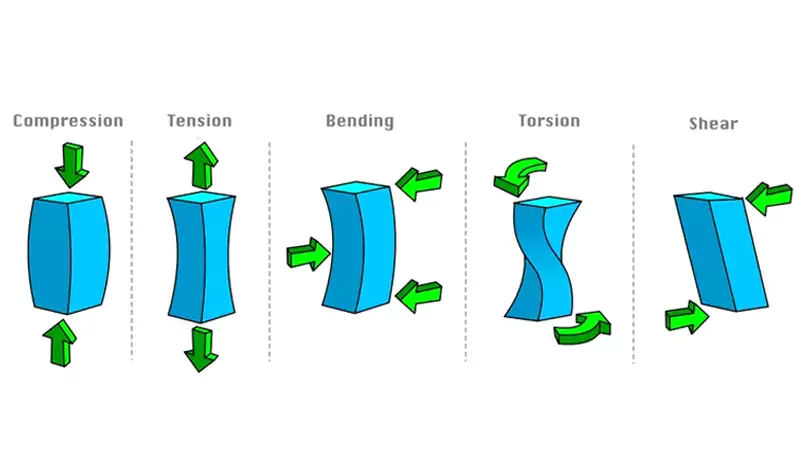

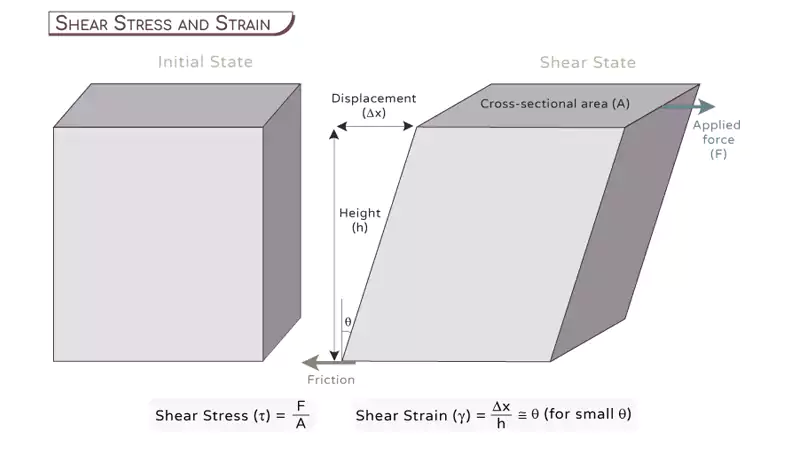

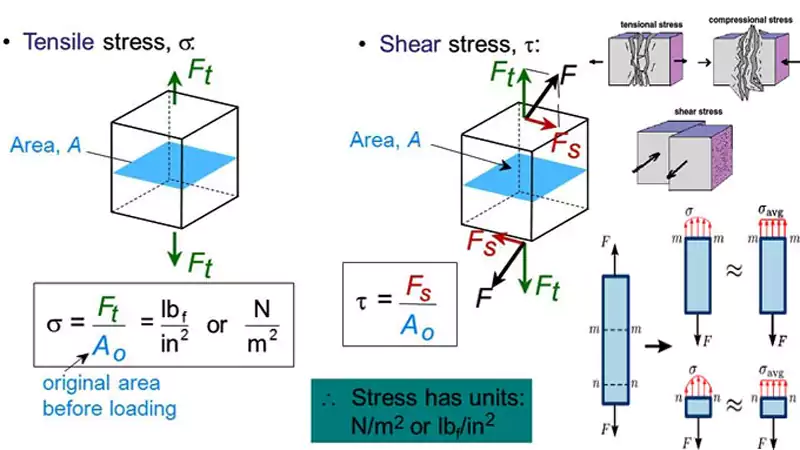

Shear stress describes how a material resists forces that try to slide one layer of metal over another, instead of pulling it apart.

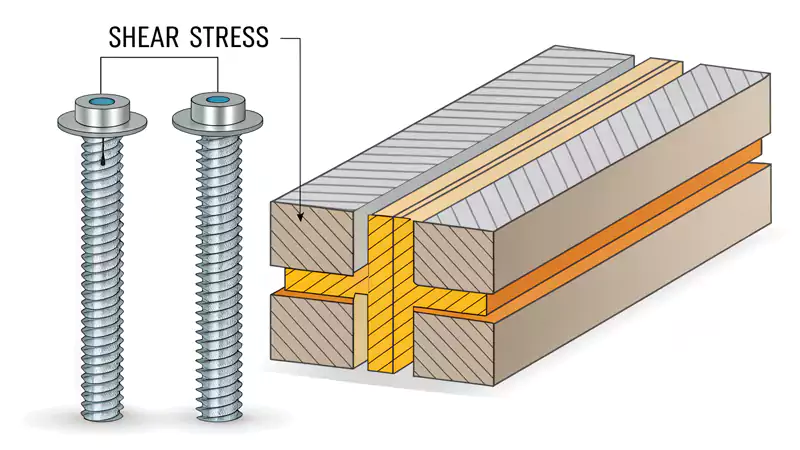

In the shop, I see shear stress whenever a part transmits torque, holds a pin, or supports a load across a small section. Unlike tensile stress, shear stress often concentrates in narrow areas. These areas include keyways, holes, fillets, and thin cast sections.

Shear Stress in Real Parts

Shear stress does not act alone. It often combines with bending and tension1. This mix makes failures harder to predict. A casting may pass tensile tests but still fail in shear because internal structure or section shape is weak.

Simple Shear vs. Real Shear

Simple shear assumes uniform force across a section. Real parts never behave this way. In castings, grain flow, porosity, and wall thickness change how shear stress spreads. I always treat textbook values as a starting point, not a final answer.

Where Does Shear Stress Occur in Real Components?

Many failures I review come from unexpected shear zones. These zones were not checked during design.

Shear stress appears in areas where force transfer happens across a section, such as pins, shafts, keys, thin walls, and joint interfaces.

In investment casting, shear stress often appears at section changes. Sharp transitions increase local stress. In machining, removing material after casting can create new shear paths that were not planned.

Common Shear Stress Locations

| Component | Typical Shear Area |

|---|---|

| Shafts2 | Keyways, splines |

| Pins & bolts | Shear planes at joints |

| Cast housings | Thin ribs and walls |

| Machined parts | Steps and slots |

I often advise designers to mark these zones early. Small changes in radius or wall thickness can reduce shear stress without adding cost.

Shear Stress vs. Tensile Stress: Key Differences for Design?

Designers often focus on tensile stress because it is easy to test. Shear stress behaves differently and needs separate attention.

Shear stress causes sliding failure along a plane, while tensile stress causes material separation along the load direction.

Materials usually resist tension better than shear. This is why many failures occur in shear even when tensile limits are not reached.

Design Implications

| Aspect | Shear Stress | Tensile Stress |

|---|---|---|

| Failure mode | Sliding or tearing | Necking or fracture |

| Sensitive to | Section shape | Material strength |

| Casting impact | Porosity critical | Grain strength critical |

In cast parts, internal defects hurt shear strength more than tensile strength. This is why quality control in casting is vital for shear-loaded parts.

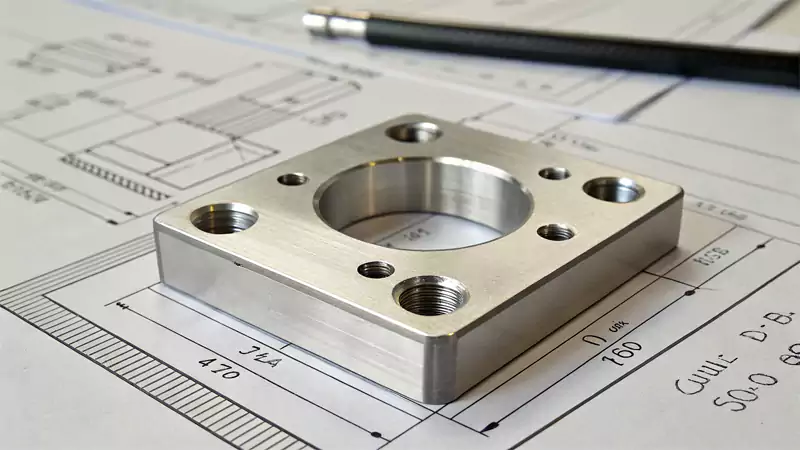

How Shear Stress Affects Cast and Machined Metal Parts?

This is where my foundry experience matters most. Casting and machining change how shear stress acts.

Shear stress in cast and machined parts is strongly influenced by internal structure, section uniformity, and post-processing steps.

Investment casting produces near-net shapes. This helps reduce machining, but it also locks in section geometry. Poor section design leads to shear failure3 later.

Case Study: Investment Cast Lever for Industrial Equipment

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Material | Stainless Steel 17-4PH |

| Process | Investment casting + CNC machining |

| Max load | 3.2 kN |

| Critical section | 6 mm thick rib |

| Failure mode | Shear crack at rib root |

| Solution | Rib thickness increased to 8 mm |

After the change, the part passed fatigue and overload tests4. No material upgrade was needed. Geometry control5 solved the problem.

Design and Manufacturing Guidelines to Control Shear Stress?

Good shear stress control starts before production. I always encourage early discussion between design and manufacturing teams.

Shear stress can be controlled through smart geometry, proper material choice, and casting-aware design decisions.

Practical Guidelines I Use

| Guideline | Reason |

|---|---|

| Avoid sharp section changes | Reduces stress concentration |

| Increase shear area | Lowers local stress |

| Use generous fillets | Improves load transfer |

| Match casting to load | Prevents hidden weak zones |

For buyers, I suggest involving the casting supplier early. Foundries understand how metal flows and solidifies. This knowledge helps reduce shear risk without adding cost or weight.

Conclusion

Shear stress is a practical design and manufacturing concern. When understood early, it helps cast and machined parts achieve better strength, reliability, and service life.

-

Exploring the interaction between bending, tension, and shear stress can enhance your knowledge of material failure mechanisms and improve design strategies. ↩

-

Learn about shaft details and how to obtain a precision custom shaft. ↩

-

Learn about shear failure to better design components and prevent costly failures in your projects. ↩

-

Understanding these tests is crucial for ensuring material durability and performance in engineering applications. ↩

-

Exploring geometry control can enhance your knowledge of precision in manufacturing processes and quality assurance. ↩